In my youth it was a juvenile joke to ask in a mock psychiatric tone, “DO YOU HEAR VOICES?”

Mature people realize there’s nothing funny about psychological suffering. But I think the joke was directed at the medical establishment’s understanding of mental discomfort instead of at the afflicted. At least, that’s how I saw it.

We shouldn’t laugh at people who suffer in mind and soul. By the same token, there’s nothing funny about how unusual psychological phenomena tend to be regarded by the medical establishment.

The tweeted article (above) seems to be headed in the right direction. But it overlooks two important factors that could play a role in hearing voices—spirituality and transpersonal psychology.

Spirituality and transpersonal psychology are usually linked. But they are not necessarily identical.

A Catholic churchgoer, for instance, may understand spirituality but knows little about transpersonal dynamics. And adherents of transpersonal psychology may have little appreciation for the Catholic belief in the Communion of Saints and the related idea of intercession.

There are many different stripes and colors among the spiritually sensitive.

So what is transpersonal psychology?

My understanding is that tangible connections among persons at a distance can be perceived by those sensitive enough to perceive them.

This can involve sensing others’ thoughts, feelings, their scent, what they see, hear, smell or physically feel. It can also involve a kind of subtle body awareness – to include sensuality and sexuality – because subtle bodies are said to interpenetrate.¹

For many people this is just New Age or Far-Eastern fantasy. And for most psychiatrists, it is simply “magical thinking.” However, for a certain percentage of the population, it is not fantasy nor delusion. For some, transpersonal psychology is quite real and far more complex and nuanced than a silly, reductive phrase like “magical thinking.”

This leads to another factor often overlooked or ridiculed by the medical establishment: The possibility of demonic deception. Quite possibly some voices could be caused by a demon messing with a person’s head.

That is a very uncool idea these days. Not in vogue. Great stuff for movies. But definitely not real. Debate over… shut the door. People who believe in demonic influence must be mentally ill.

That is, the medical trumps the spiritual paradigm.

Why does the medical establishment mostly turn a blind eye to spirituality and transpersonal psychology? Presumably this is because the majority of its practitioners are too worldly and conceptually biased to appreciate the subtler, finer aspects of life.

Some doctors might go to church, temple or mosque. But it is doubtful that they sense higher (and lower) mystical states to any great or advanced degree.² If they did, they would probably be monks, sisters or hermits instead of medical professionals.

Hence the mainstream dismissal of important spiritual possibilities.

Funnily enough, when I first became interested in Catholicism a priest pointed to his heart and confided in me by saying, “I hear a voice, right here.” He may have been speaking figuratively, but from our conversation he seemed to be saying that this voice tells him what is from God and what is not from God, and also serves to guide him.

Being a smart guy, this priest keeps his ‘voice’ under wraps. If that kind of terminology got out, his enemies might brand him a so-called schizophrenic, which could hinder his ability to help others.

Be wise as serpents and harmless as doves ~ Matthew 10:16

For the most part, psychiatric theories have a pretty firm grip on the public imagination. Many folks parrot the latest trends and politically influenced classifications as if they were the Gospel Truth.

The medieval Church once controlled others through fear and persecution. Today, science exerts its own kind of ideological influence. But the control is so pervasive and complete that most are hardly aware of it. They conform. They believe what the doctor tells them.

You don’t think so?

Take a look at sites like Quora.com and read how some individuals completely accept medical explanations (and labels) given for their psychological suffering. Some almost seem to enjoy playing the role of “good patient.” They praise their doctors for illuminating the “truth” about their illness. And they seem oblivious to alternative explanations.

Sadly, when alternative explanations are ignored, healthier remedies could also be ignored.

So instead of experimenting with, say, the Catholic Eucharist as well as attitudinal and behavioral changes for the better, sufferers take the latest medications on the market.

God only knows how those medications (arguably a euphemism for drugs) may affect the rest of their body. Long term side-effects (arguably a euphemism for harmful effects) are often downplayed but a quick reading of scientific journals reveals that known harmful effects can be debilitating, even lethal.

Let me be clear: I am not anti-meds. If drugs help a person to cope or if they protect innocents from potentially violent individuals, they probably should be administered. But I believe drugs should always be taken with a view toward finding a better solution.

We must consider alternatives and critically assess the medical and religious ideologies of our time. An integrative approach that includes medical science and spiritual teachings would probably be optimal.

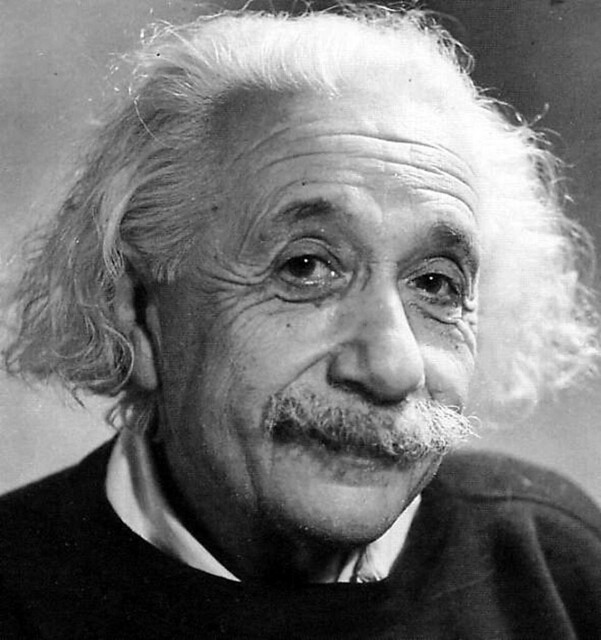

Science without religion is lame, religion without science is blind ~ Albert Einstein

—

¹ In Eastern philosophy, this involves the doctrines of adhyasa (superimposition) and karma transfer. This kind of interior perception could also include sensing the spiritual environment and influences associated with another person. In contemporary parlance, good or bad vibes.

² The academic study of religion terms this the numinous, after Rudolf Otto‘s and later, Carl Jung‘s adaptation of the Latin numen. Some say that numen is based on the Greek nooúmenon. The English term first appears in 1647.

Although many people are skeptical about anything related to the supernatural and spiritism—considering them to be either a hoax or the product of the film industry’s creative scriptwriters—the Bible presents a different view. It provides explicit warnings about spiritism. The Bible tells us that long before God formed the earth, he created millions of spirit creatures, or angels. (Job 38:4, 7; Revelation 5:11) Each of these angels was endowed with free will—the ability to choose between right and wrong. Some of them chose to rebel against God, and they abandoned their position in heaven to cause trouble on the earth. As a consequence, the earth became “filled with violence.”—Genesis 6:2-5, 11; Jude 6. People should be cautious about paranormal and supernatural powers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I couldn’t agree with you more. This piece mostly critiques “medical materialism” as C. G. Jung once put it. But an equally pointed critique could be made against those who uncritically accept all things paranormal.

I added this in the final paragraph to show that I realize its importance too. But I didn’t dwell on it. Not here. Elsewhere at earthpages.ca I try to apply a healthy skepticism to many parapsychological issues, as we all should.

Thanks for your comment. 🙂

LikeLike